Understanding POCSO And Why Lowering The Age Of Consent Below 18 Is Dangerous

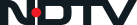

Bhuwan Ribhu

New Delhi: When India enacted the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO) 2012, it transformed how our justice system viewed minor victims of sexual violence. By declaring any sexual activity involving someone under 18 as a punishable offence, POCSO established a firm boundary: no child can legally consent. It mandated speedy, sensitive procedures and placed the burden of proof on the accused. Through POCSO, India sent out a message that protecting children is a priority. Lately, there has been renewed debate that treating all under-18 relationships alike wrongly equates innocent teenage love with crime, and that the “age of consent” should be lowered to 16. However, before we debate shifting the line to 16, we must first understand the act's purpose, its framework, the arguments for lowering the consent age and the risks of doing so. Only then can we come up with solutions that acknowledge adolescent realities without compromising child protection.

What Is POCSO And How It Protects Children

POCSO, which is the primary law against child sexual abuse, goes far beyond defining rape. It categorises a range of sexual offences against children: penetrative assault, aggravated assault, sexual harassment, child pornography, grooming and trafficking for sexual purposes. It imposes some of the toughest penalties, with particularly severe terms for penetrative and aggravated assaults.

The offences under the Act are cognizable and non-bailable. The police can arrest without a warrant. However, there are no specific statutory guidelines on granting bail. Bail decisions rest on judicial discretion, where courts weigh constitutional liberties against potential risk to the child.

By shifting the burden of proof onto the accused and fast-tracking child complaints, POCSO builds a safety net at every step of investigation and adjudication.

The threshold of 18 years aligns with several statutes to maintain legal consistency. Under the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, minors accused of POCSO offences face juvenile courts and receive rehabilitation-centred dispositions unless an inquiry deems the crime “heinous”. The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act 2006 deems any marriage below 18 void. The Indian Majority Act and Indian Contract Act fix full legal capacity at 18, in line with India's commitments under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Since 18 is the non-negotiable threshold for consent, any sexual act involving a person under 18 is an offence, even if the relationship was voluntary. This creates a legal grey zone when adolescents engage in consensual relationships that later lead to prosecution. Advocates for lowering the age of consent argue that the Act is too punitive and overlooks adolescent autonomy. They point to countries where the age of consent ranges from 14 to 16, often accompanied by “close-in-age” or “Romeo and Juliet” provisions that protect consensual relationships between teenagers while still punishing coercion, exploitation and large age gaps. However, what works there won't necessarily work in India, where social conditions, education and protection frameworks are very different.

India Has Not Defined an Age of Consent

Introducing consent will open a Pandora's box, legitimising various forms of child rape, including trafficking and child marriage. Lowering the age of consent would erode deterrence by suggesting consent is negotiable. A trafficker or abuser could claim sexual activity was consensual simply because the minor was over 16.

Children aged 16 to 18 years face larger vulnerability when it comes to grooming, manipulation and coercion. They lack emotional maturity to grasp the meaning or consequences of consent. Their brains, specifically regions governing impulse control and risk evaluation, continue developing into their mid-20s. While they may have the physical capacity for sexual activities, their brains may not yet be fully developed to make informed decisions about giving or refusing consent.

Judicial Discretion and Case-by-Case Safeguards

Genuine adolescent relationships do exist, but the law cannot be blind to context. With appropriate checks and balances, it is possible to ensure protection without undermining safeguards. In the context of judicial discretion, considerations could include a romantic relationship of at least two years, an age difference of less than three years, no history of trafficking, exploitation, blackmail, or threat, consistent statements by the minor before the Child Welfare Committee and in court corroborated by a support person, a complaint filed by someone other than the minor, and no complaint of gang rape or prior criminal history.

Implementation Gaps That Demand Urgent Action

POCSO remains India's strongest legal safeguard against child sexual offences. However, before considering amendments to the law, the priority must be its full and effective implementation. Currently, over 200,000 cases are pending in special courts that are severely understaffed and under-resourced. Conviction rates are below 10%, and compensation is awarded in less than 1% of cases. From slow forensic processes and lack of child-friendly environments to inconsistent appointment of support persons and trials extending beyond the mandated 12- month period, victims face numerous obstacles on the long road to justice.

Emphasis on Prevention and Protection

In Just Rights for Children Alliance v. S Harish (2024), the Supreme Court recognised the complex and evolving nature of child sexual exploitation. The Court called for a systemic framework that goes beyond prosecution and emphasises prevention, rehabilitation and coordination to safeguard children.

The Court gave the following suggestions to the Centre:

- First, implement comprehensive sex education programs that should dispel misconceptions and give young people a clear understanding of consent and the impact of sexual exploitation.

- Second, provide support services to victims and rehabilitation programs for offenders, including psychological counselling, therapeutic interventions that focus on recognising harm and correcting distorted thinking.

- Third, launch public awareness campaigns to destigmatise reporting and encourage community vigilance.

- Fourth, identify at-risk individuals early and implement intervention strategies for youth exhibiting problematic sexual behaviours (PSB). This requires coordinated efforts among educators, healthcare providers, law enforcement and child welfare services. Professionals across these fields should receive training to spot warning signs and respond appropriately.

- Fifth, empower schools to play a critical role in early identification and intervention through programs that teach healthy relationships, consent and appropriate behaviour.

Children must be taught the meaning of consent, the right to say no and the importance of respecting others' boundaries. A clear understanding of what is criminal, what is simply wrong and what is unacceptable behaviour is crucial to helping them make sense of the world around them. These early lessons form a protective shield, enabling children to speak up and seek help.

Lowering the age of consent from 18 to 16 would undo years of progress in protecting children from sexual exploitation, abuse and trafficking. The way forward is not dilution, but full enforcement of POCSO, with the urgency and seriousness this crisis demands.

(Bhuwan Ribhu is a child rights activist, advocate, and author working to end impunity against child sexual abuse and exploitation through the Just Rights for Children network)

Stories

- Bhuwan Ribhu | Monday August 18, 2025

Lowering the age of consent risks weakening child protection, and instead India must focus on fully enforcing POCSO with stronger preventive measures

- Bhuwan Ribhu | Monday August 18, 2025

Human trafficking is the second-largest crime in the world. It generates $150 billion a year, according to global estimates

- NDTV | Monday July 28, 2025

India fights against child labour through strong legal action, community support, and the PICKET strategy

- Rachna Tyagi | Wednesday July 30, 2025

India's POCSO victims face delayed, inadequate compensation; urgent, uniform national schemes are vital for justice and survivor rehabilitation

- Rachna Tyagi | Monday June 16, 2025

AI-generated abusive content like deep-fake manipulation and other emerging forms like Webcam Child Sex Tourism (WCST) are on the rise

- Devyani Madaik | Friday July 25, 2025

For over two decades, Bhuwan Ribhu's legal fight against child exploitation earned him the World Jurist Association's Medal of Honour

- Bhuwan Ribhu | Wednesday July 30, 2025

Auspicious Akshaya Tritiya, meant for prosperity, sadly marks child marriages, a tragic misfortune for our daughters

- Pandit Deepak Dubey | Wednesday April 30, 2025 , नई दिल्ली

कन्या दान को पुण्य कार्य इसलिए माना जाता है क्योंकि पिता से लगाव होता है. यानी इसमें पिता स्नेह का त्याग करता है. इसका बाल विवाह से कहीं लेना-देना नहीं है. हालांकि अभी भी कुछ जगहों पर बाल विवाह की कुप्रथाएं हैं. बाल विवाह अभिशाप है.

- Bhuwan Ribhu | Saturday March 22, 2025

Who will guard the guardians when the custodians of justice bring their own interpretations to override what the law - the will of the people laid down by Parliament - clearly provides?

- Just Rights For Children | Saturday March 22, 2025 , New Delhi

Child labour in the incense manufacturing industry, a longstanding concern for India, is declining significantly and the sector is moving towards complete freedom from child labour in Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Bihar, a study finds.